Love harder

Love Harder (2022-ongoing, Türkiye, Malta, France, Morocco) is a long term project exploring a new perspective on the relationship between queerness and religion in the conservative cultural Mediterranean region.

People, as complex, multi-faceted individuals, should not have to choose between their religion, cultural background and sexual orientation or gender.

‘Identities are multiple and coexist within a single person, a single body.’

This project is mapping the multiplicity of possibilities that many patriarchal cultures try to deny, using portraiture, landscape, interviews and research from specialists in the field.

Each portrait is a photograph of someone who is queer (either by their sexual orientation or by their gender, or both.), and who were raised in a religious cultural environment, some of whom embraced it, some of whom rejected it.

Through these multiple layers, Love Harder is a quest for acceptance against uniformity imposed by their culture. By carving spaces for intersectionality not only to exist, but also to flourish.

I met Dal in 2018 in Paris, where he lives. At the time, considering his multiplicity of identites - being trans, Algerian, Kabyle and Muslim - he told me that if someone asked him to mix water with oil, he could do it.

In the Parisian summer of 2022, Dal is sunbathing on his balcony. He wears the qamis, a traditionnal outfit for men found accross the Middle East. His father brought it back for him from his pilgrimage to Mecca. Dal was particularly pleased with this gift, a man's qamis, which symbolises his father's acceptance and love for his trans son.

When my father brought me this gift back from his pilgrimage, I understood the power of faith. Faith is love of oneself and of others.' Paris, 2022

‘If you are gay, I will kill you’

A father to his son

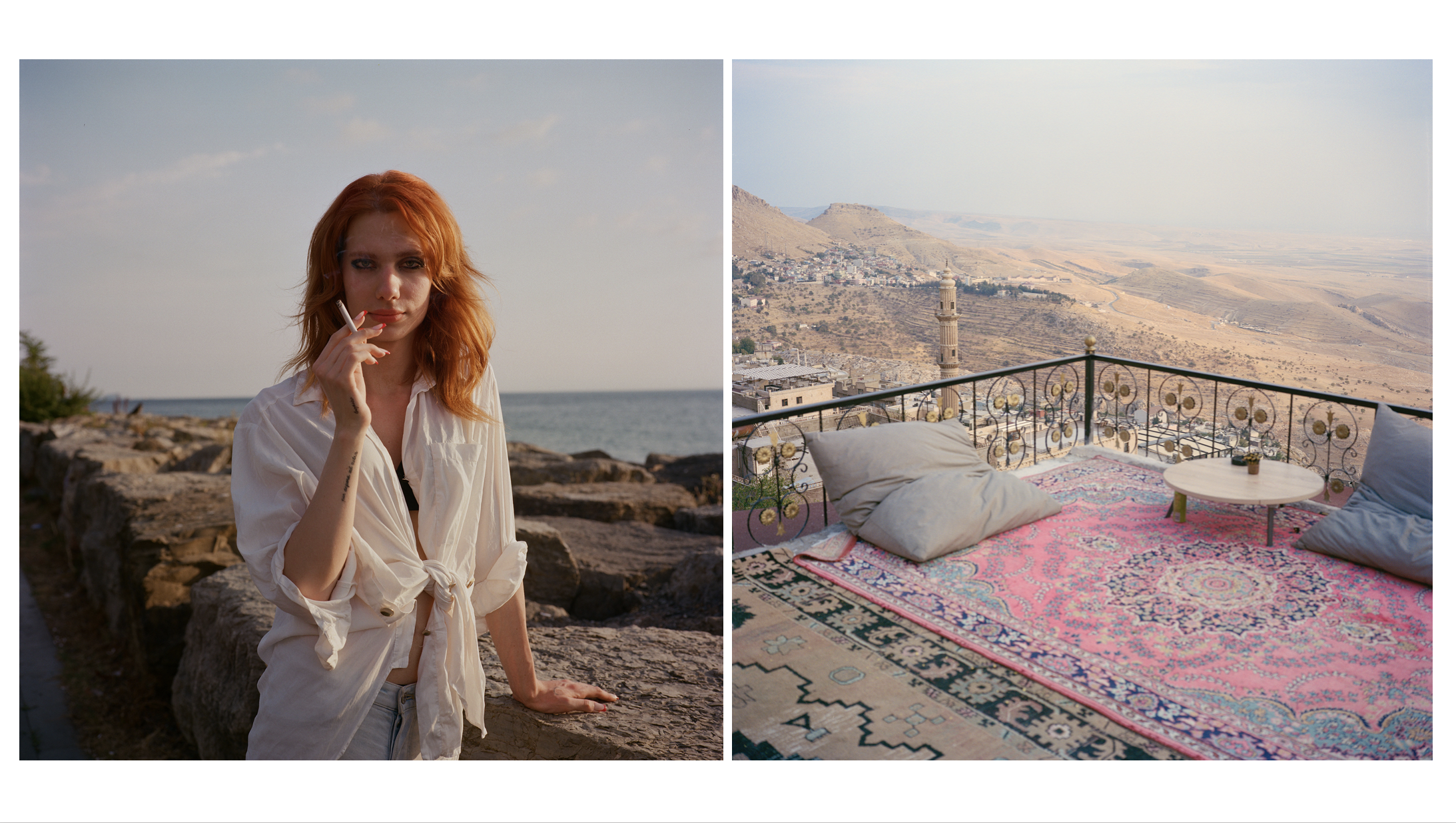

Kerem and Mecnun met 2 years ago and as same sex union is not recognized in Türkiye, they got married with their friends. Mecnun grew up in Mardin, a conservative town in the South East of Anatolia. He hasn’t come out to his family because they are very homophobic. They told him they would kill him if he was gay.

Kerem got kicked out by his father after he came out at a young age and had to interrupt his studies to support himself. His father still refuses to talk to him, but his mother, a deeply religious woman, supports him to be himself. She became a feminist and an activist for LGBTQIA+ rights.

Kerem and Mecnun live together in a conservative district of Istanbul and their landlord, who lives above their apartment, thinks they are just housemates.

Istanbul, 2023

Elif is a young woman from Sanliurfa, a conservative and religious town in the South East of Anatolia. She works for a feminist NGO. She started to get involved for muslim women to have access to better spaces in the mosques.

Recently a constitution change that guarantees women’s right to wear the hijab was proposed in Türkiye.

'Within the same article that proposes the women’s right to wear the hijab, they defined the family in a very heterosexual way. They’re paving the way for more discrimination against LGBTQIA+ people. What does this have to do with my hijab? It’s only a political thing.

It makes it very complicated for people like me because you have to choose sides if you want to exist in this narrative. I refuse to do that.

Both can be a part of anyone’s identity, not just mine. You may want to wear the hijab someday in your life, it should be your right as a queer person. Or I may want to take it off. I may want to change my gender expression or define my sexual orientation differently. This is a very made up rhetoric discourse that you have to chose only one thing. It also makes the queer community take a position against me, against people who wear the hijab. So that’s a very big problem.

It’s very easy to assume things and put labels on me because I’m visible.’ Elif, Istanbul, 2023

The progressive Imam Ludovic Mohammed Zahed, who is married to a man and opened the first inclusive mosque in Paris, had his conference in Türkiye canceled due to death threats.

‘ We all had a period of distance where it’s very difficult to combine queerness and religion in a society that is becoming more and more essentialist and where identities are performatives. This dichotomy is redondant in people’s personal stories, where they have to choose between gender, sexuality and religion.

It’s a dogmatic, social and patriarcal pressure that exists outside of Islam. There’s nothing about the queer question in the Koran. It says that different identities were represented, and that feminine men should be respected.’ Ludovic Mohammed Zahed.

In his country of origin ( Algeria), ‘promotion of homosexuality’ can lead to prison.

‘Istanbul is so important to me, my identity, my style. I feel like I have its map internalized. Being yourself and being queer in this Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, Asia Minor country, you should find and create your own alternative spaces to be able to survive and proliferate. It’s not just about sustaining yourself but spreading. Learning how to manifest, and flourish.'

Misra, Istanbul, 2023

Romeo and Samantha are twins who live together in Malta. Romeo transitionned two years ago and tattooed himself during this time, to choose what to add to his body. The chest piece says : Love Harder in Maltese.

'I have been shielding myself, wearing a lot of protective gear. I’m a shape shifter.’ says Romeo.

His sister Samantha suffered from anorexia for years. Body dysphoria and body dysmorphia are close to each other. They’re both inoculated by patriarchy. She has tattooed the symbol of the butterfly, used both for her disease and for trans people.

Mariah, Malta, 2023

Reda, a 26 years old Moroccan artist told me that by the age of four, he was already able to clearly get hold of his queerness: ‘I just did not have a name for it until junior high, through conversations with friends or names I had been called. It did not intimidate me one bit and strangely enough, I never felt shame or the urge to hide myself and cosplay something I was not.’ ‘ Religion is something he sees as ‘intimate, cherished and protected away from any kind of external inference or moralizing entity. A personal shrine of all the things your soul stands for. I refuse to separate or compartmentalize the feminine and the masculine: life feels more bountiful and generous this way.’ Reda

Tanger, Morocco, 2024

‘As a gay man in a society torn between its roots and the vibrant spectrum of human love, I become a symbol of defiance and acceptance. Amidst the disapproving whispers and piercing stares, there is a fierce determination within me, a flame of authenticity that refuses to be extinguished. Istanbul has become both my battleground and sanctuary.’

.

Mert having tea in a traditional tea house in Karaköy, Istanbul, area where he feels safe as a gay man. He just graduated as a doctor and dreams of emigrating to the U.K. to be free to get married with his boyfriend who is already there. Istanbul, 2023